A Comprehensive Survey of Recommendation Algorithms: From Collaborative Filtering to Large Language Models

September 6, 2025

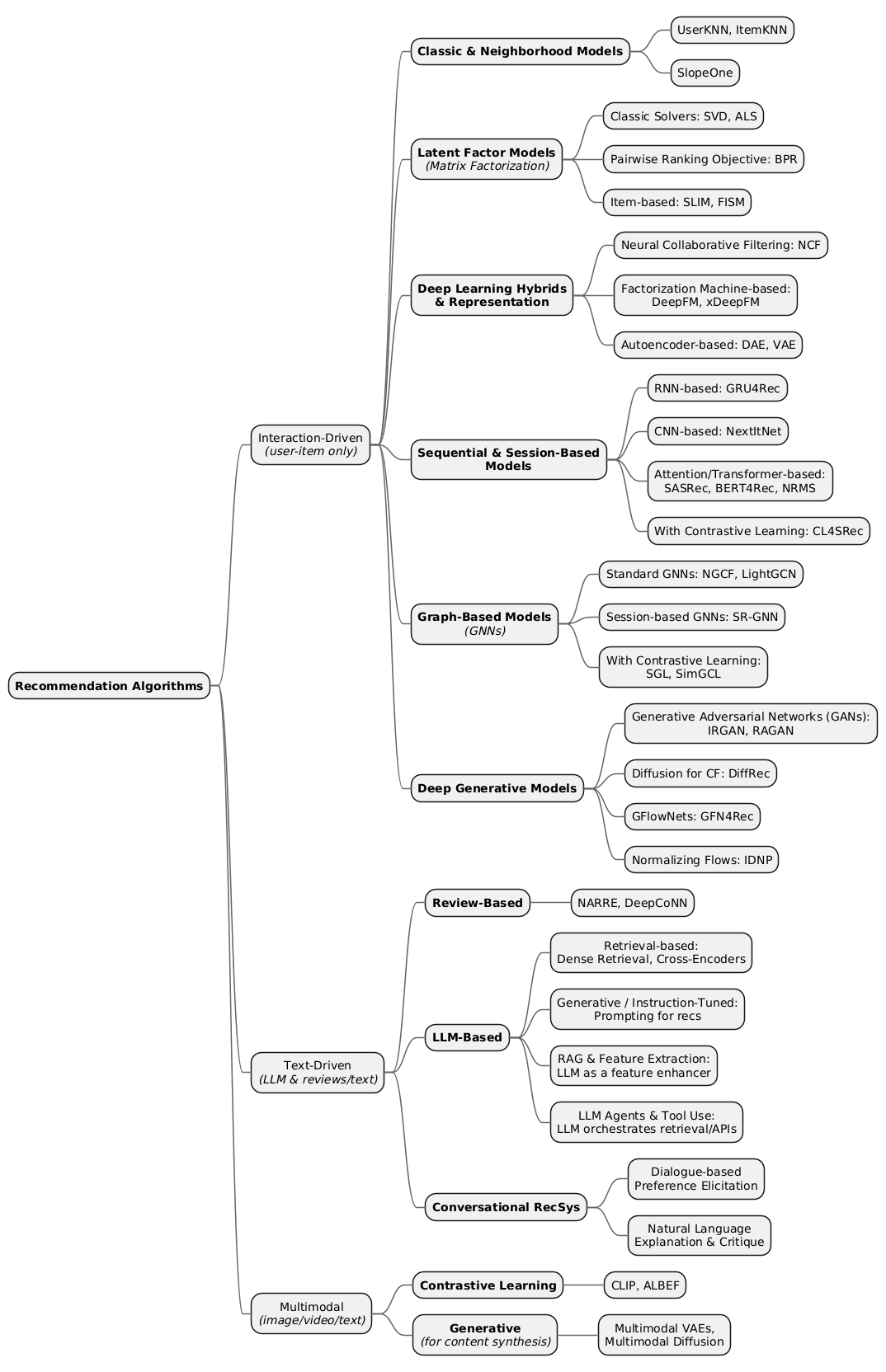

Download PDFThis paper provides a systematic and exhaustive review of recommendation algorithms, charting their evolution from foundational collaborative filtering techniques to the sophisticated deep learning and generative models of the modern era. We organize the landscape into three primary categories based on the dominant data modality: Interaction-Driven, Text-Driven, and Multimodal algorithms. For each paradigm and its key algorithms, we distill the core concepts, highlight key differentiators, identify primary use cases, and offer practical guidance for implementation. Our analysis reveals a recurring tension between model complexity and performance, the transformative impact of self-supervised learning, and the paradigm-shifting potential of Large Language Models. This survey is intended as a cornerstone reference for engineers and researchers seeking to navigate the complex, dynamic, and powerful field of recommender systems.

IMPORTANT: The structure and content of this blog post partially overlap with my book Recommender Algorithms, but it is far, far behind in terms of detail and depth of explanations. Many concepts are explained in the book more thoroughly and accessibly. I don’t rule out the possibility that some inaccuracies in the post below were corrected in the book—I simply didn’t have the energy to work on both the book and keeping this post up to date. On the book’s page, you can view the first 40 pages and form your own impression.

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Section 1: Interaction-Driven Recommendation Algorithms

- Section 2: Text-Driven Recommendation Algorithms

- Section 3: Multimodal Recommendation Algorithms

- Conclusion

Abstract

This paper provides a systematic and exhaustive review of recommendation algorithms, charting their evolution from foundational collaborative filtering techniques to the sophisticated deep learning and generative models of the modern era. We organize the landscape into three primary categories based on the dominant data modality: Interaction-Driven, Text-Driven, and Multimodal algorithms. For each paradigm and its key algorithms, we distill the core concepts, highlight key differentiators, identify primary use cases, and offer practical guidance for implementation. Our analysis reveals a recurring tension between model complexity and performance, the transformative impact of self-supervised learning, and the paradigm-shifting potential of Large Language Models. This survey is intended as a cornerstone reference for engineers and researchers seeking to navigate the complex, dynamic, and powerful field of recommender systems.

Introduction

In the modern digital ecosystem, users are confronted with a virtually infinite selection of items, from products and movies to news articles and music. This phenomenon, often termed “information overload,” presents a significant challenge for both consumers and platforms. Recommender systems have emerged as a critical technology to address this challenge, serving as personalized information filters that guide users toward relevant content, thereby enhancing user experience, engagement, and commerce.

The field of recommendation algorithms has undergone a remarkable evolution. Early systems were built on simple statistical methods that leveraged direct user-item interactions. These foundational techniques, known as collaborative filtering, gave way to more sophisticated latent factor models, which sought to uncover the hidden dimensions of user preference by decomposing the user-item interaction matrix. The deep learning revolution subsequently ushered in a new era, with neural networks enabling the modeling of complex, non-linear relationships that were previously intractable.

This progression continued with the development of specialized architectures to capture the sequential dynamics of user behavior, borrowing heavily from advances in natural language processing. Concurrently, a new perspective emerged that modeled the recommendation problem as a graph, applying Graph Neural Networks to capture high-order relationships between users and items. Most recently, the landscape is being reshaped by the advent of large-scale generative models, including Generative Adversarial Networks, Diffusion Models, and, most notably, Large Language Models (LLMs), which are redefining the boundaries of what recommender systems can achieve.

This paper aims to provide a structured, high-level, and practical overview of this algorithmic landscape. We organize our survey into three principal sections based on the primary data modality each class of algorithms leverages:

-

Interaction-Driven Algorithms: Models that rely exclusively on user-item interaction data (e.g., ratings, clicks, purchases).

-

Text-Driven Algorithms: Models that incorporate unstructured text, such as user reviews or item descriptions, and are increasingly powered by LLMs.

-

Multimodal Algorithms: Models that fuse information from multiple sources, such as text, images, and video, to create a holistic understanding of items and preferences.

For each algorithm, we provide a concise explanation of its core concept, key differentiators, primary use cases, and practical considerations for implementation, along with a link to its seminal paper. Our objective is to equip engineers and researchers with a comprehensive map to navigate the field, understand its historical trajectory, and make informed decisions when designing and deploying the next generation of recommender systems.

Section 1: Interaction-Driven Recommendation Algorithms

These algorithms rely solely on user-item interaction data, such as ratings, clicks, or purchases, without incorporating additional content like text or images. They focus on patterns in how users engage with items to make predictions, forming the foundation of collaborative filtering.

1.1 Classic & Neighborhood-Based Models

These are foundational “memory-based” collaborative filtering approaches that recommend items based on similarities between users or items. They operate directly on the user-item interaction matrix, are simple, interpretable, and work well with sparse data but can struggle with scalability, coverage, and cold-start issues in very large or sparse datasets. They serve as powerful baselines for more complex models.

1.1.1 UserKNN (User-based k-Nearest Neighbors)

UserKNN (User-based K-Nearest Neighbors) finds users similar to the target user based on their interaction histories (using similarity measures like cosine or Pearson correlation on rating vectors) and recommends items that those similar users liked.

Key concept: It assumes similar users have similar tastes, enabling predictions from “neighbors.”

Key differentiator: Focuses on user similarities, making it intuitive for scenarios where user preferences are stable and interpretability is key (e.g., explaining recommendations via “Users who liked X also liked Y”).

Use cases: E-commerce sites for personalized suggestions based on similar shoppers, or early recommender systems like GroupLens. Consider it when you have a moderate number of users, ample interaction data, and want quick, explainable recommendations without deep learning overhead.

-

Seminal Papers:

-

GroupLens: an open architecture for collaborative filtering of netnews. Resnick, Paul and Iacovou, Neophytos and Suchak, Mitesh and Bergstrom, Peter and Riedl, John. 1994. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/192844.192905.

-

On the challenges of studying bias in Recommender Systems: A UserKNN case study. Savvina Daniil, Manel Slokom, Mirjam Cuper, Cynthia C.S. Liem, Jacco van Ossenbruggen, Laura Hollink. https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.08046

-

1.1.2 ItemKNN (Item-based k-Nearest Neighbors)

ItemKNN (Item-based K-Nearest Neighbors) recommends items similar to those the user has interacted with in the past, based on item similarity computed from user interactions (often using adjusted cosine similarity to account for user biases).

Key concept: It builds item similarity matrices, assuming users tend to like items similar to ones they’ve liked before.

Key Differentiator: More scalable than UserKNN for large item catalogs since item similarities change less frequently; offers transparency via “Because you watched X, you might like Y.”

Use cases: Streaming services like Netflix for “similar to what you’ve watched,” or Amazon’s early item-based recommender for efficient, real-time suggestions. Consider it when your item set is stable, data is sparse, and you need efficient computation with reasonable accuracy and minimal training.

-

Seminal Papers:

-

Item-based collaborative filtering recommendation algorithms, Sarwar, Badrul and Karypis, George and Konstan, Joseph and Riedl, John., 2001. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/371920.372071

-

On the challenges of studying bias in Recommender Systems: A UserKNN case study. Savvina Daniil, Manel Slokom, Mirjam Cuper, Cynthia C.S. Liem, Jacco van Ossenbruggen, Laura Hollink. https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.08046

-

1.1.3 SlopeOne

SlopeOne is a simple, non-iterative algorithm that predicts ratings by computing average deviations (or “slopes”) between item pairs, assuming linear relationships like f(x) = x + b, where b is the pre-computed average rating deviation.

Key concept: It models consistent offsets in ratings (e.g., if Item B is rated 0.5 higher than Item A on average, predict accordingly for a new user); new ratings can update averages incrementally.

Differentiator: Extremely lightweight with no training phase (O(n²) preprocessing for n items), handles cold-start better than KNN, and supports dynamic updates with fast queries.

Use cases: Quick prototyping, mobile apps, or online systems with limited resources where numerical ratings exist and simplicity/speed trump top accuracy. Consider it when preferences have consistent offsets, you need an incremental model, or engineering overhead must be minimal.

Python Frameworks

-

Surprise https://surpriselib.com/: Provides robust implementations for explicit data, including KNNBasic, KNNWithMeans, and KNNWithZScore, allowing for various baseline and normalization strategies.

-

scikit-learn https://scikit-learn.org/: While not a dedicated recommender library, its NearestNeighbors module is a common choice for implementing the core similarity search component of a k-NN recommender.

Production-ready?

Item-based k-NN, in particular, is a proven, scalable, and effective algorithm that has been a cornerstone of production recommender systems for years. It is famously used by companies like Amazon for their “customers who bought this also bought” feature, demonstrating its real-world utility. While it remains a powerful tool, especially as a baseline or a component in a hybrid system, it can face challenges with data sparsity and, in the case of user-based variants, scalability issues as the number of users grows.

For the Slope One, it is different. The primary advantages of Slope One are its ease of implementation, low storage requirements, and extremely fast prediction time. These characteristics make it an excellent choice for systems with limited computational resources, as a strong and simple-to-debug baseline, or in online settings where the model needs to be updated frequently and dynamically as new ratings arrive.

1.2 Latent Factor Models (Matrix Factorization)

These “model-based” methods address data sparsity by decomposing the user-item interaction matrix into lower-dimensional latent factor matrices for users and items. The core idea is to represent users and items in a shared latent space where their proximity reflects preference. This condenses complex interaction patterns into a small number of hidden features, moving beyond direct neighbor comparisons to uncover the underlying reasons for preferences.

Simply put…

It’s like creating a “taste profile” for both users and items using the same set of hidden characteristics.Imagine you’re recommending movies. Instead of just knowing which movies a person likes, the model tries to figure out why. It creates a handful of underlying characteristics, like “amount of sci-fi,” “level of comedy,” or “degree of romance.”

Each movie gets a score for each of these characteristics. For example, a rom-com would score high on “comedy” and “romance” but low on “sci-fi.” Each user gets a matching profile based on the movies they’ve enjoyed. Someone who loves rom-coms would get high scores for “comedy” and “romance” preferences. To make a recommendation, the system just finds movies whose characteristic scores are a great match for the user’s preference scores. This way, it can recommend a new movie the user has never seen, as long as its “taste profile” fits theirs.

1.2.1 Classic Solvers: SVD & ALS

Key concept: These techniques represent each user and item as a vector of latent factors, which capture underlying characteristics (e.g., for movies, a factor might represent the “action vs. drama” dimension). The predicted rating is then calculated as the dot product of their respective latent vectors.

For example, a user who scores high on the “prefers action” factor will have a high predicted rating for a movie that scores high on the “is an action movie” factor. The model learns these factor vectors by minimizing the prediction error on known ratings.

Key differentiator: The main difference lies in the optimization method.

- SVD (Singular Value Decomposition), in the context of recommendation, typically refers to models trained with Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD). This method iteratively adjusts the factors to minimize prediction error. It’s flexible but can be slow on very large datasets.

- ALS (Alternating Least Squares) works by fixing one set of factors (e.g., all user vectors) and solving a standard least-squares problem for the other set (all item vectors), and then alternating. This process is highly parallelizable, making ALS more scalable in distributed environments like Spark. It is also particularly effective for implicit feedback data, where interactions are treated as positive signals with varying confidence levels.

Use cases: These models are workhorses for personalized recommendation, primarily for predicting explicit ratings (e.g., 1-5 stars) in domains like e-commerce (such as Amazon) and media streaming (such as Netflix). ALS is dominant in industrial settings with very large, sparse datasets that require distributed training.

When to Consider: Matrix factorization is a powerful step up from neighborhood models, especially for sparse data. Use an SVD-like model (trained with SGD) when you need a flexible model and are comfortable with iterative training. Opt for ALS when dealing with large-scale, sparse datasets, especially if you have access to a distributed computing framework. ALS is particularly effective for implicit feedback scenarios when using a weighted formulation (WR-ALS).

Matrix factorization is a technique to break down a large user-item interaction matrix (like ratings or clicks) into two smaller matrices that represent users and items in a shared “taste” space. By finding hidden patterns in the data, it assigns scores to users and items based on latent features (e.g., “love for sci-fi” or “preference for comedy”). These scores help predict how much a user will like an item they haven’t interacted with, making recommendations more accurate.

- Seminal Papers:

- SVD (in RecSys context): Koren, Y., Bell, R., & Volinsky, C. (2009). Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/220381329_Matrix_factorization_techniques_for_recommender_systems.

- ALS: Zhou, Y., Wilkinson, D., Schreiber, R., & Pan, R. (2008). Large-scale Parallel Collaborative Filtering for the Netflix Prize. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/221566136_Large-scale_Parallel_Collaborative_Filtering_for_the_Netflix_Prize.

1.2.2 Pairwise Ranking Objective: BPR (Bayesian Personalized Ranking)

Key concept: BPR reframes the recommendation problem from predicting a score (rating prediction) to predicting a preference order (ranking). It operates on a pairwise assumption: for a given user, an item they have interacted with (a positive item) should be ranked higher than an item they have not interacted with (a negative item). The model is trained to maximize this probability for pairs of items.

Key differentiator: This represents a crucial maturation of the field. Early models focused on optimizing metrics like RMSE, which measures the accuracy of predicting a specific rating value (e.g., 3.7 stars vs. 3.8). However, the practical value of a recommender lies in its ability to place the most relevant items at the top of a list. BPR was a landmark development because it aligned the model’s optimization objective directly with this business goal of creating a high-quality ranked list, making it ideal for implicit feedback data (clicks, purchases) where there are no negative examples, only unobserved ones.

Use cases: BPR is the standard for modeling implicit feedback data where the goal is to produce a ranked list of recommendations (Top-N recommendation). It is widely used in e-commerce, media streaming, and any domain where explicit ratings are unavailable or sparse but interaction data is plentiful.

When to Consider: An engineer should choose BPR whenever the primary goal is to generate a ranked list of items rather than predict ratings. By learning to correctly order pairs of items, it directly improves the quality of the ranked list, a far more meaningful outcome for the end-user. This makes BPR or other ranking-based loss functions the default choice for any Top-N recommendation task based on implicit feedback.

- Seminal Paper:

- Rendle, S., Freudenthaler, C., Gantner, Z., & Schmidt-Thieme, L. (2009). BPR: Bayesian personalized ranking from implicit feedback. https://arxiv.org/abs/1205.2618.

1.2.3 Item-based Latent Models: SLIM & FISM

Key concept: These models combine the interpretability of item-based methods with the power of latent factor models. Instead of relying on simple co-occurrence statistics, they learn an item-item similarity matrix directly from the interaction data using a machine learning model.

Key differentiator:

- SLIM (Sparse Linear Methods) learns a sparse item-item similarity matrix ($W$) by solving a regression problem. A user’s score for an item is a weighted sum of their interactions with other similar items. The sparsity (enforced by L1 regularization) makes the model efficient and interpretable—each item’s score is influenced by only a few other items.

- FISM (Factored Item Similarity Models) takes a hybrid approach. Instead of learning the full item-item similarity matrix directly, it factorizes it into two lower-dimensional item embedding matrices. This allows it to learn transitive relationships (e.g., if item A is similar to B, and B is similar to C, then A and C might be similar) even if A and C were never co-rated, making it more powerful on extremely sparse datasets.

Use cases: Both models are designed for Top-N recommendation from implicit feedback. SLIM is highly effective and efficient, making it a strong baseline and suitable for production systems where speed and interpretability are critical. FISM is particularly advantageous in scenarios with very high data sparsity, where learning latent relationships is crucial.

When to Consider: Choose SLIM when you need a fast, scalable, and interpretable item-based model that often outperforms more complex methods. It’s an excellent choice when you want a “learned” item-item similarity model. Consider FISM when facing extreme data sparsity. Its ability to generalize and find similarities between items that do not co-occur in the training data gives it a distinct advantage in such challenging scenarios.

- Seminal Papers:

- SLIM: Ning, X., & Karypis, G. (2011). SLIM: sparse linear methods for top-n recommender systems. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/220765374_SLIM_Sparse_Linear_Methods_for_Top-N_Recommender_Systems.

- FISM: Kabbur, S., Badrul, S., & Karypis, G. (2013). FISM: factored item similarity models for top-n recommender systems. http://chbrown.github.io/kdd-2013-usb/kdd/p659.pdf.

Python Frameworks

-

Surprise https://surpriselib.com/: Offers popular and well-documented implementations of SVD, Probabilistic Matrix Factorization (PMF), and SVD++, an extension that incorporates implicit feedback.

-

implicit https://github.com/benfred/implicit: This library’s primary focus is on high-performance matrix factorization for implicit data, providing highly optimized implementations of ALS and BPR

-

Cornac https://github.com/preferredAI/cornac-ab Includes implementations of PMF and other MF variants as part of its comparative framework

-

RecTools https://github.com/MobileTeleSystems/RecTools Provides wrappers and its own implementations of matrix factorization models

-

RecBole https://github.com/RUCAIBox/RecBole Provides an implementation of SLIM under the name SLIMElastic, which incorporates the elastic net regularization used in the original paper

Production-ready?

Matrix factorization is one of the most influential and widely deployed techniques in the history of recommender systems. Its ability to generalize from sparse data by learning latent representations made it a breakthrough technology, famously popularized by its success in the Netflix Prize competition. It remains a core component of many large-scale production systems and serves as the conceptual foundation for many advanced deep learning architectures, such as Neural Collaborative Filtering.

SLIM and its variants have demonstrated very strong performance in academic studies for the top-N recommendation task, often outperforming more complex methods. However, they are less commonly seen as standalone models in production systems compared to matrix factorization or k-NN. Their principles have influenced subsequent research, and they serve as powerful baselines for evaluating new item-based recommendation algorithms.

1.3 Deep Learning Hybrids & Representation Learning

This category marks the transition from linear latent factor models to more expressive, non-linear models powered by neural networks. By replacing the simple dot product with deep learning architectures, these models can capture more complex and subtle user-item interaction patterns that traditional methods might miss.

What are non-linear relationships?

Think of it like this: a linear model assumes that if you like action movies twice as much, you’ll get twice the enjoyment from an action scene. A non-linear model understands that the relationship is more complex. Maybe you love action movies, but after two hours, your enjoyment plateaus or even drops. Neural networks are excellent at learning these kinds of nuanced, “it depends” relationships from the data automatically.

1.3.1 Neural Collaborative Filtering (NCF)

Key concept: NCF is a framework that generalizes Matrix Factorization (MF) by replacing its dot product with a neural network. Instead of just multiplying user and item latent vectors, NCF concatenates them and feeds them through a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). This allows the model to learn an arbitrary, complex interaction function between users and items.

Key differentiator: Its primary advantage is the ability to capture complex, non-linear patterns in the data. While standard MF is restricted to a linear combination of factors, NCF can model synergistic effects—for example, it can learn that a user’s preference for the “sci-fi” genre and the “Christopher Nolan” director together creates a much stronger signal than the sum of the individual preferences.

Use cases: NCF is a general-purpose model for collaborative filtering from implicit feedback. It is used for Top-N recommendation in various domains where user-item interactions might have complex patterns that matrix factorization cannot capture.

When to Consider: Consider using NCF when you suspect that the underlying user-item interactions are too complex to be modeled by a simple dot product. If standard matrix factorization models are hitting a performance plateau, NCF is a logical next step to introduce non-linearity and increase model expressiveness, provided you have enough data to train a deeper model without overfitting.

- Seminal Paper:

- He, X., Liao, L., Zhang, H., Nie, L., Hu, X., & Chua, T. S. (2017). Neural Collaborative Filtering. https://arxiv.org/abs/1708.05031.

1.3.2 Factorization Machine-based: DeepFM & xDeepFM

Key concept: These models are advanced hybrid architectures designed primarily for Click-Through Rate (CTR) prediction. They combine a “wide” component for learning simple, memorable feature interactions and a “deep” component for learning complex, generalizable patterns. Both components share the same input embeddings, making training highly efficient.

What is Click-Through Rate (CTR) Prediction?

CTR prediction is the task of estimating the probability that a user will click on an item (like an ad, a product, or a news article) if it is shown to them. It’s a critical task in online advertising and recommendation, as it directly relates to engagement and revenue. Models that are good at CTR prediction excel at understanding what makes a user click in a specific context.

Key differentiator:

- DeepFM combines a Factorization Machine (FM) for the “wide” part and a standard MLP for the “deep” part. The FM component is highly effective at learning 2nd-order feature interactions (e.g., how the combination of “user is a teenager” and “item is a video game” affects clicks) without manual effort.

- xDeepFM (eXtreme DeepFM) improves upon this by replacing the standard MLP with a Compressed Interaction Network (CIN). The CIN is specifically designed to explicitly learn high-order feature interactions in a more controlled, vector-wise manner, which can be more powerful and interpretable than the implicit interactions learned by an MLP.

Use cases: Both models are state-of-the-art for CTR prediction in large-scale industrial recommender systems, such as those used in online advertising, e-commerce, and news feeds. They are designed to handle high-dimensional, sparse, and multi-field categorical features (e.g., user demographics, item category, time of day).

When to Consider: You may consider these models for any feature-rich recommendation task, especially CTR prediction. DeepFM is a powerful and widely used baseline. However, if you believe that explicit, high-order feature combinations are particularly important in your domain (e.g., “young user” + “sports category” + “weekend”), xDeepFM’s CIN component offers a more targeted mechanism for learning them.

- Seminal Papers:

- DeepFM: Guo, H., Tang, R., Ye, Y., Li, Z., & He, X. (2017). DeepFM: A Factorization-Machine based Neural Network for CTR Prediction. https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.04247.

- xDeepFM: Lian, J., Zhou, X., Zhang, F., Chen, Z., Xie, X., & Sun, G. (2018). xDeepFM: Combining Explicit and Implicit Feature Interactions for Recommender Systems. https://arxiv.org/abs/1803.05170.

1.3.3 Autoencoder-based: DAE & VAE

Key concept: This approach frames collaborative filtering as a reconstruction task. It takes a user’s entire interaction history (e.g., a sparse vector of all items they’ve clicked on) as input and trains a neural network—the autoencoder—to compress this information into a dense low-dimensional latent vector and then reconstruct the original interaction vector from it.

What is an Autoencoder?

An autoencoder is a type of neural network trained to learn a compressed representation of its input data. It has two main parts: an encoder that maps the input to a low-dimensional “bottleneck” representation, and a decoder that tries to reconstruct the original input from this compressed version. By forcing data through this bottleneck, the network learns the most important and salient features.

Key differentiator:

- DAE (Denoising Autoencoder) for CF learns robust representations by being trained to reconstruct the original, complete user history from a partially corrupted input (e.g., some of the user’s clicks are randomly set to zero). This forces the model to learn the underlying relationships between items to “fill in the blanks.”

- VAE (Variational Autoencoder) for CF is a probabilistic, generative model. Instead of mapping a user to a single latent vector, it maps them to a full probability distribution. This allows it to better capture the uncertainty and multi-modal nature of user preferences (e.g., a user’s taste might be “80% comedy fan, 20% drama fan”).

Use cases: These models are highly effective for Top-N recommendation from implicit feedback. VAE-CF, in particular, has become a very strong and widely used baseline for collaborative filtering, often achieving state-of-the-art results on benchmark datasets.

When to Consider: Consider using an autoencoder-based model when linear latent factor models are insufficient. DAEs are a good choice for learning robust representations from noisy interaction data. VAEs are an even stronger choice for implicit feedback Top-N tasks, as their probabilistic nature and multinomial likelihood objective are exceptionally well-suited for the ranking problem. They are a go-to model for researchers and practitioners aiming for top performance in collaborative filtering.

- Seminal Papers:

- DAE (for RecSys): Wu, Y., DuBois, C., Zheng, A. X., & Ester, M. (2016). Collaborative Denoising Auto-Encoders for Top-N Recommender Systems. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2835776.2835837.

- VAE (for RecSys): Liang, D., Krishnan, R. G., Hoffman, M. D., & Jebara, T. (2018). Variational Autoencoders for Collaborative Filtering. https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.05814.

Python Frameworks

-

Tensorflow https://github.com/tensorflow/tensorflow The TensorFlow Model Garden includes an official implementation and tutorial for building an NCF model

- Microsoft Recommenders https://github.com/recommenders-team/recommenders: Provides a detailed Jupyter notebook implementation of NCF, explaining both the theory and practical application. Also includes an example notebook for xDeepFM.

- Cornac https://github.com/PreferredAI/cornac Features an implementation of BiVAECF (Bilateral Variational Autoencoder for Collaborative Filtering)

- RecBole https://recbole.io/docs/user_guide/model/context/deepfm.html Provides implementations of both DeepFM and xDeepFM

- LibRecommender https://github.com/massquantity/LibRecommender Offers a TensorFlow-based implementation of DeepFM with extensive configuration options

Production-ready?

NCF is a seminal deep learning model for recommendation that has had a significant impact on the field. It is widely used in industry, both as a powerful standalone model and as a strong baseline for evaluating more advanced architectures. Its core architectural principles have influenced the design of many subsequent models.

VAE-based models for collaborative filtering, particularly the Mult-VAE variant which uses a multinomial likelihood objective, have proven to be highly effective and often achieve state-of-the-art results on academic benchmarks. They are used in production systems, but also remain a very active area of research, with new extensions being developed for multimodal data , interactive critiquing , and multi-criteria recommendation.

DeepFM and xDeepFM are considered state-of-the-art models for tabular CTR prediction and are widely deployed in production systems for applications like computational advertising, feed ranking, and product recommendation.

1.4 Sequential & Session-Based Models

This paradigm marks a fundamental shift from treating user interactions as an unordered set to modeling them as an ordered sequence. The goal is to predict the user’s next action based on the temporal dynamics of their recent behavior. This shift reflects a powerful conceptual convergence with the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP), where a sequence of user interactions is treated analogously to a sequence of words in a sentence.

Why does order matter?

Imagine a shopping session. A user who clicks on “iPhone -> iPhone Case -> Screen Protector” has a very clear and different intent from a user who clicks on “iPhone -> Laptop -> Headphones.” The first user is accessorizing a specific product, while the second is browsing different categories. Sequential models are designed to understand these ordered patterns to make much more contextually relevant “what’s next” predictions.

1.4.1 RNN-based: GRU4Rec

Key concept: GRU4Rec was a pioneering model that applied Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) to session-based recommendation. It processes a sequence of user interactions one by one, maintaining a “memory” or hidden state that evolves with each new item. This state captures the user’s current intent, which is then used to predict the very next item they are likely to interact with.

What is an RNN?

A Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) is a type of neural network designed for sequential data. Think of it as having a short-term memory. As it reads a sequence (like words in a sentence or items in a session), it passes information from one step to the next. This allows it to understand context and order, making it perfect for predicting what comes next based on what happened before. The GRU (Gated Recurrent Unit) is an advanced and efficient type of RNN.

Key differentiator: Its core innovation was using RNNs to handle variable-length, anonymous user sessions. Unlike static models, GRU4Rec captures the evolving nature of user intent within a single session. It also introduced ranking-aware loss functions to directly optimize for the quality of the recommended list, not just prediction accuracy.

Use cases: GRU4Rec is designed for session-based recommendation, where user identity may be unknown or irrelevant (e.g., guest shoppers). It is common in e-commerce for predicting the next product click, in media streaming for the next song or video, and in news for the next article.

When to Consider: GRU4Rec is a strong baseline for any sequential or session-based task where short-term context and the order of interactions are critical. It’s particularly useful when a user’s intent evolves throughout a session and you need to make real-time, next-step predictions.

- Seminal Paper:

- Hidasi, B., Karatzoglou, A., Baltrunas, L., & Tikk, D. (2016). Session-based Recommendations with Recurrent Neural Networks. https://arxiv.org/abs/1511.06939.

1.4.2 CNN-based: NextItNet

Key concept: NextItNet applies Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), traditionally used for image processing, to model sequences of user interactions. It treats an embedded sequence of items as a 1D “image” and uses stacked layers of dilated convolutions to efficiently identify patterns and long-range dependencies.

How can a CNN work on a sequence?

Imagine the sequence of items is laid out like a single row of pixels. A CNN applies “filters” that slide across this row to recognize local patterns (e.g., “item A is often followed by item B”). By using dilated convolutions, which skip inputs at varying rates, the network can create a very large receptive field, allowing it to see how an item at the beginning of a long session influences an item at the end, all without the step-by-step processing of an RNN.

Key differentiator: The main advantage of NextItNet over RNNs is efficiency and parallelism. CNNs can process all parts of a sequence simultaneously, making training much faster. Its use of dilated convolutions and residual blocks allows it to build very deep networks that can capture dependencies across extremely long sequences (hundreds of items) where RNNs might struggle with vanishing gradients.

Use cases: NextItNet is used for session-based and sequential Top-N item recommendation. It is particularly well-suited for scenarios with very long user interaction sequences and where training efficiency on large datasets is a major concern.

When to Consider: Consider NextItNet when training speed is a priority or when dealing with very long sequences where capturing long-range dependencies is crucial. It represents a powerful and scalable architectural alternative to RNNs for modeling sequential data.

- Seminal Paper:

- Yuan, F., Karatzoglou, A., Arapakis, I., Jose, J. M., & He, X. (2019). A Simple Convolutional Generative Network for Next Item Recommendation. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3289600.3290975.

1.4.3 Attention/Transformer-based: SASRec & BERT4Rec

Key concept: This family of models leverages the self-attention mechanism, the core component of the Transformer architecture that has revolutionized NLP. Self-attention allows the model to dynamically weigh the importance of all other items in a sequence when making a prediction for the next item, overcoming the sequential processing bottleneck of RNNs and the fixed receptive field of CNNs.

What is Self-Attention?

Self-attention is a mechanism that allows a model to look at other items in the input sequence and decide which ones are most important for understanding the current item. For recommendation, this means that to predict your next action, the model can pay more attention to the very first item you clicked on, or a specific item you lingered on, regardless of its position in the sequence. It learns to identify the most influential past actions on the fly.

Key differentiator: The key innovation is the use of self-attention, providing a global view of the sequence. The distinction between the two main models is crucial:

- SASRec (Self-Attentive Sequential Recommendation) is unidirectional (autoregressive). It only considers past items to predict the future, strictly respecting the temporal flow of user actions. It excels at identifying which of the previous items are most relevant for the next choice.

- BERT4Rec (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers for Recommendation) is bidirectional. Inspired by BERT in NLP, it is trained using a “cloze task” where it predicts a randomly masked item in the sequence using both its left and right context (items that came before and after). This allows it to learn a richer, more holistic representation of user interests.

Use cases: These models represent the state-of-the-art for sequential recommendation tasks. SASRec is a powerful general-purpose model for next-item prediction. BERT4Rec is particularly effective when a user’s overall interest is a reflection of their entire history, not just a linear progression. NRMS is a specialized variant for news recommendation that uses attention to model both the content of articles and the sequence of articles read.

When to Consider: Transformer-based models should be the default choice for high-performance sequential recommendation. Choose SASRec for tasks where strict temporal order is paramount. Consider BERT4Rec when you have dense data and believe a user’s intent is better captured by their holistic interaction history.

- Seminal Papers:

- SASRec: Kang, W. C., & McAuley, J. (2018). Self-Attentive Sequential Recommendation. https://arxiv.org/abs/1808.09781.

- BERT4Rec: Sun, F., Liu, J., Wu, J., Pei, C., Lin, X., Ou, W., & Jiang, P. (2019). BERT4Rec: Sequential Recommendation with Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformer. https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.06690.

1.4.4 With Contrastive Learning: CL4SRec

Key concept: CL4SRec is a framework that enhances sequential models by adding a contrastive self-supervised learning objective. In addition to the primary task of predicting the next item, the model is trained to recognize that two different augmented views of the same user sequence should have similar representations, while being distinct from the sequences of other users.

What is Contrastive Learning?

Contrastive learning is a technique where a model learns by comparing things. You teach it what makes two things similar and what makes them different. For sequential recommendation, you take a user’s interaction history, create two slightly modified versions of it (e.g., by hiding or cropping a few items), and tell the model: “These two augmented sequences represent the same underlying preference, so their representations should be close. Push them away from the representations of all other sequences.” This helps the model learn the essential, robust essence of a user’s taste.

Key differentiator: Its key innovation lies in designing data augmentation strategies specifically for user interaction sequences (e.g., Item Crop, Item Mask). This self-supervised task acts as a powerful regularizer, forcing the model to learn more robust and generalizable user representations, which is especially helpful in sparse data scenarios.

Use cases: CL4SRec is used to enhance any underlying sequential recommendation model (like SASRec). It is particularly effective in scenarios with high data sparsity or noisy interactions, as the additional self-supervised signal helps the model learn meaningful user representations from limited data.

When to Consider: Consider integrating a contrastive learning framework like CL4SRec when your sequential model is underperforming due to data sparsity or overfitting. It can significantly boost performance by forcing the model to learn the core semantic properties of a user’s preference sequence, often improving recall for long-tail items.

- Seminal Paper:

- Xie, X., Sun, F., Liu, Z., Wu, J., Zhang, H., & Lin, X. (2020). Contrastive Learning for Sequential Recommendation. https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.14395.

Python Frameworks

- GRU4Rec:

- RecBole: https://github.com/RUCAIBox/RecBole Provides a well-maintained implementation.

- Microsoft Recommenders: https://github.com/recommenders-team/recommenders Includes a notebook demonstrating a GRU-based model for sequential recommendation.

- The original authors maintain a Theano implementation https://github.com/pascanur/theano_optimize and strongly caution against using unverified third-party versions.

- NextItNet https://github.com/fajieyuan/WSDM2019-nextitnet:

- RecBole: https://github.com/RUCAIBox/RecBole Includes a supported implementation.

- Microsoft Recommenders: https://github.com/recommenders-team/recommenders Provides a notebook showcasing its application.

- SASRec & BERT4Rec:

- RecBole https://github.com/RUCAIBox/RecBole & SELFRec: https://github.com/Coder-Yu/SELFRec Offer robust implementations of both models.

- Transformers4Rec (NVIDIA): https://github.com/NVIDIA-Merlin/Transformers4Rec A powerful library designed to adapt HuggingFace Transformers for recommendation tasks, providing an excellent environment for experimenting with these models.

- CL4SRec:

- SELFRec: https://github.com/Coder-Yu/SELFRec A Python framework specifically designed for self-supervised recommendation, featuring CL4SRec as one of its flagship implementations.

Production-ready?

- GRU4Rec: While often surpassed by Transformers on benchmarks, it remains a powerful and relevant baseline. Its recurrent nature can be more efficient during real-time inference for step-by-step predictions, making it a viable production choice.

- NextItNet: A strong and efficient model. Its parallelizable convolutional architecture makes it a competitive choice for production systems, especially for its ability to model long sequences effectively.

- SASRec & BERT4Rec: State-of-the-art and Production-Ready. These models represent the cutting edge for sequential recommendation. Their effectiveness has led to their increasing adoption in industrial production systems at major tech companies.

- CL4SRec: Rapidly moving from Research to Production. Contrastive learning has consistently demonstrated significant performance improvements on academic benchmarks. Its proven ability to enhance model robustness and alleviate data sparsity makes it highly attractive, and its principles are being rapidly integrated into the training pipelines of production models.

1.5 Graph-Based Models (GNNs)

These models represent the user-item interaction data as a bipartite graph—a graph with two sets of nodes (users and items)—where an edge connects a user to an item they have interacted with. They then apply Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to learn user and item embeddings, explicitly modeling the collaborative filtering effect by propagating information through this graph structure.

What is a Bipartite Graph in Recommendation?

Imagine two groups of dots. One group represents all your users, and the other represents all your items. You draw a line (an edge) between a user and every item they’ve clicked on, rated, or purchased. The result is a bipartite graph. A GNN can “walk” along these lines to discover patterns. For example, by walking from

User A -> Item 1 -> User B, the model learns that User A and User B have similar tastes, which is the core idea of collaborative filtering.

1.5.1 Standard GNNs: NGCF & LightGCN

Key concept: These models refine user and item embeddings through a process of neighborhood aggregation or message passing. The core idea is that a user’s embedding should be influenced by the items they have interacted with, and an item’s embedding by the users who have interacted with it. By stacking multiple GNN layers, the model can capture high-order relationships, allowing influence to propagate across multiple “hops” in the graph (e.g., from a user to the users-who-liked-similar-items).

Key differentiator: The key difference lies in their complexity and approach to aggregation.

- NGCF (Neural Graph Collaborative Filtering) was a seminal model that used complex feature transformations and non-linear activation functions in each GNN layer to model intricate relationships.

- LightGCN is its simplified and more powerful successor. The authors found that the feature transformations and non-linearities in NGCF were not essential for collaborative filtering and could even hinder performance. LightGCN removes them, focusing purely on weighted neighborhood aggregation. This simplification makes it faster, less prone to overfitting, and often significantly more accurate.

Use cases: Both models are designed for standard collaborative filtering tasks from implicit feedback. They are used for Top-N recommendation and have shown state-of-the-art performance on many benchmark datasets. LightGCN, due to its simplicity and effectiveness, has become a very strong and widely used baseline for graph-based recommendation.

When to Consider: Graph-based models are a powerful choice when you want to capture the collaborative signal more explicitly than in standard matrix factorization. Start with LightGCN. Its simplicity, strong performance, and efficiency make it an excellent choice for most CF tasks. It serves as a crucial lesson: targeted simplicity often trumps general-purpose complexity.

- Seminal Papers:

- NGCF: Wang, X., He, X., Wang, M., Feng, F., & Chua, T. S. (2019). Neural Graph Collaborative Filtering. https://arxiv.org/abs/1905.08108.

- LightGCN: He, X., Deng, K., Wang, X., Li, Y., Zhang, Y., & Wang, M. (2020). LightGCN: Simplifying and Powering Graph Convolution Network for Recommendation. https://arxiv.org/abs/2002.02126.

1.5.2 Session-based GNNs: SR-GNN

Key concept: SR-GNN models a user’s session as a small, dynamic graph. For each session sequence, it constructs a directed graph where each unique item is a node and edges connect consecutively clicked items. A Gated Graph Neural Network is then applied to this session graph to learn complex item transition patterns. Finally, it uses the embeddings of items in the session to predict the next item.

Key differentiator: While sequential models like RNNs process interactions in a strict linear order, SR-GNN can capture more complex, non-sequential relationships within a session. For example, in a session [Phone -> Case -> Charger], it can directly model the relationship between “Phone” and “Charger” through the graph structure, a connection that an RNN might only capture weakly. This makes it more robust to user behaviors like clicking back and forth between items.

Use cases: SR-GNN is used for session-based recommendation, particularly in anonymous settings (e.g., for users who are not logged in) where the goal is to predict the next action based only on the interactions in the current session.

When to Consider: Consider SR-GNN when you are working with session data and believe the relationships between items are more like a web than a straight line. If a user’s behavior within a session is not strictly linear, a graph-based representation can capture these richer dependencies more effectively than a purely sequential model.

- Seminal Paper:

- Wu, S., Tang, Y., Zhu, Y., Wang, L., Xie, X., & Tan, T. (2019). Session-Based Recommendation with Graph Neural Networks. https://arxiv.org/abs/1811.00855.

1.5.3 With Contrastive Learning: SGL & SimGCL

Key concept: This line of work enhances GNN-based recommenders by incorporating a self-supervised, contrastive learning objective. The model learns to generate robust embeddings by ensuring that different augmented “views” of the same user or item are pulled closer together in the embedding space, while being pushed apart from other users or items.

Key differentiator: The innovation lies in the data augmentation strategy used to create the “views.”

- SGL (Self-supervised Graph Learning) creates views by applying structural perturbations to the graph itself, such as randomly dropping nodes or edges. This makes the model’s embeddings robust to missing or noisy interaction data.

- SimGCL (Simple Contrastive Learning on Graphs) uses a much simpler and often more effective technique: it creates views by adding a small amount of random noise directly to the embeddings during training. This avoids the complexity of graph manipulation while achieving a similar regularization effect.

Use cases: These methods are used to improve the performance and robustness of GNN-based collaborative filtering models like LightGCN. They are particularly effective for alleviating popularity bias and improving performance on sparse datasets where the additional self-supervised signal acts as a strong regularizer.

When to Consider: An engineer should consider using a contrastive learning framework to enhance a GNN-based recommender, especially if the model suffers from popularity bias or performs poorly on long-tail items. Given its simplicity and superior efficiency, SimGCL is an excellent starting point.

- Seminal Papers:

- SGL: Wu, J., Wang, X., Feng, F., He, X., Chen, L., Lian, J., & Xie, X. (2021). Self-supervised Graph Learning for Recommendation. https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.10783.

- SimGCL: Yu, J., Yin, H., Xia, X., Chen, T., Cui, L., & Nguyen, Q. V. (2022). Are Graph Augmentations Necessary? Simple Graph Contrastive Learning for Recommendation. https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.08679.

Python Frameworks

- NGCF & LightGCN:

- RecBole (https://github.com/RUCAIBox/RecBole): Provides high-quality, configurable implementations of both NGCF and LightGCN.

- Agent4Rec https://github.com/LehengTHU/Agent4Rec A recent research framework on generative agents for recommendation uses LightGCN as one of its pre-trained model options

- Microsoft Recommenders (https://github.com/recommenders-team/recommenders): Provides a detailed “deep dive” notebook on LightGCN, explaining its theory and implementation.

- The original authors of LightGCN maintain a PyTorch implementation at https://github.com/kuandeng/LightGCN.

- SR-GNN:

- Implementations are available in major frameworks like RecBole and in various public GitHub repositories.

- SGL & SimGCL:

- RecBole includes an implementation for SGL.

- The authors of SimGCL provide a PyTorch implementation at https://github.com/Coder-Yu/RecQ.

Production-ready?

- LightGCN: Production-Ready and State-of-the-art Baseline. Its simplicity, efficiency, and strong performance make it one of the most powerful and widely used baselines for collaborative filtering. It is heavily used in both academia and industry.

- SR-GNN: A strong, production-viable model for its specific niche of session-based recommendation. It is a go-to choice when session dynamics are complex and non-linear.

- SGL & SimGCL: Rapidly moving from Research to Production. The principles of contrastive learning on graphs have proven to be highly effective at improving model robustness. While still an active area of research, these techniques are being integrated into production pipelines to boost the performance of GNN-based systems, especially in sparse data environments.

- NGCF was a breakthrough paper that demonstrated the immense potential of GNNs for collaborative filtering. However, its architecture, which includes feature transformation matrices and non-linear activation functions at each layer, has since been shown to be overly complex for the CF task. It is now primarily considered a foundational work and is used as a key baseline in research to evaluate newer, more streamlined GNN architectures.

1.6 Deep Generative Models

This frontier of research moves beyond discriminative models to generative models, which learn the underlying probability distribution of the data. This allows them to generate plausible user interaction histories or novel item recommendations, rather than just predicting a score for a given user-item pair.

Discriminative vs. Generative Models: What’s the difference?

It’s like the difference between a music critic and a composer.

- A Discriminative model is the critic. You give it a user and a song, and it discriminates by giving a score or a probability: “This user will like this song with 85% probability.” It learns the boundary between what a user likes and dislikes.

- A Generative model is the composer 🎼. You give it a user, and it generates a new playlist from scratch that it thinks the user will love. It learns the underlying patterns and structure of a user’s taste so well that it can create new examples.

1.6.1 Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): IRGAN

Key concept: IRGAN adapts the GAN framework to recommendation by setting up a competitive game between two neural networks:

- A Generator, which acts as the recommender. It tries to learn the true distribution of a user’s preferences and generates “fake” (user, item) pairs that it predicts are relevant.

- A Discriminator, which acts as a critic. It is trained to distinguish between the “fake” items suggested by the Generator and the actual items from the user’s real interaction history.

Through this adversarial training, the Generator is forced to produce increasingly realistic recommendations to “fool” the Discriminator, thereby learning a more robust model of user preferences.

Key differentiator: The adversarial training process itself is unique. It creates a dynamic optimization landscape where the Generator effectively performs “hard negative mining” by trying to find the most challenging examples to fool the Discriminator. This can help the model learn to recommend more diverse and novel items, overcoming biases in the training data.

Use cases: IRGAN is a general framework applicable to web search, item recommendation, and other information retrieval tasks. It’s used to learn the distribution of user preferences and generate a ranked list of items, with the potential to improve coverage of long-tail items.

When to Consider: Consider exploring GANs for research-oriented projects or when traditional models seem to be underperforming due to data bias. While conceptually powerful, GAN-based recommenders are notoriously difficult and unstable to train, which has limited their widespread adoption in production.

- Seminal Paper:

- Wang, J., Yu, L., Zhang, W., Gong, Y., Xu, Y., Wang, B., Zhang, P., & Zhang, D. (2017). IRGAN: A Minimax Game for Unifying Generative and Discriminative Information Retrieval Models. https://arxiv.org/abs/1705.10513.

1.6.2 Diffusion for CF: DiffRec

Key concept: DiffRec adapts the powerful Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) from image generation to recommendation. The process has two stages:

- Forward (Diffusion) Process: It starts with a user’s true interaction vector (e.g., a multi-hot vector of liked items) and gradually adds Gaussian noise over a series of steps, eventually corrupting it into pure noise.

- Reverse (Denoising) Process: A neural network is trained to reverse this process. It learns to take a noisy vector at any step and predict the noise that was added, thereby iteratively denoising it back to the original, clean interaction vector.

To generate recommendations, the model starts with random noise and, conditioned on a user’s profile, runs this reverse process to generate a new, plausible interaction vector.

Key differentiator: The iterative denoising process is a fundamentally different generative paradigm from GANs or VAEs. It is often more stable to train than GANs and can model highly complex data distributions, leading to high-quality and diverse generated outputs. This makes it particularly well-suited for capturing the uncertainty and multi-modal nature of user preferences.

Use cases: DiffRec is a generative model for Top-N recommendation from implicit feedback. Its strength lies in its ability to model complex preference distributions and its robustness to noisy interactions in the training data.

When to Consider: Consider DiffRec when you need a powerful generative model that can capture complex user preferences and where recommendation diversity and novelty are key objectives. It represents the cutting edge of generative modeling, but be mindful that it is computationally intensive, especially during the iterative sampling process at inference time.

- Seminal Paper:

- Wang, W., Feng, F., He, X., Wang, X., & Wang, Q. (2023). Diffusion Recommender Model. https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.04971.

1.6.3 GFlowNets: GFN4Rec

Key concept: GFN4Rec uses Generative Flow Networks (GFlowNets) to frame recommendation as a sequential decision problem. It learns to construct a list of recommended items step-by-step. The model is trained to ensure that the probability of generating a particular list is directly proportional to a predefined reward function (e.g., the predicted overall quality or utility of that list).

Key differentiator: Unlike most models that score items individually, GFN4Rec directly optimizes for the utility of an entire slate of recommendations. Its training objective inherently promotes diversity; if two different lists yield a similar high reward, the GFlowNet learns to assign both a high probability of being generated, rather than collapsing to a single “best” list.

Use cases: GFN4Rec is specifically designed for listwise recommendation tasks where both the relevance and diversity of the recommended set are important. It is well-suited for online environments where exploration and the discovery of novel good recommendations are valuable.

When to Consider: Consider GFN4Rec when the business objective is to optimize for the utility of an entire slate, not just individual item clicks. If recommendation diversity is a key performance indicator, GFN4Rec’s intrinsic diversity-promoting objective makes it a very compelling choice over models trained with standard cross-entropy loss.

- Seminal Paper:

- Liu, J., Jin, Z., Liu, D., He, X., & McAuley, J. (2023). Generative Flow Network for Listwise Recommendation. https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.02239.

1.6.4 Normalizing Flows: IDNP

Key concept: Normalizing Flows are a class of generative models that learn a complex data distribution by applying a series of invertible and differentiable transformations to a simple base distribution (e.g., a standard Gaussian). Because every step is perfectly reversible, they can calculate the exact likelihood of any data point, a property not shared by VAEs or GANs.

Key differentiator: The ability to compute the exact log-likelihood makes Normalizing Flows a principled and powerful tool for precise density estimation. In the context of recommendation, a related model like IDNP (Interest Dynamics Neural Process) uses this concept to model a distribution over a user’s preference function over time, allowing it to capture uncertainty and generalize from very few data points.

Use cases: In recommendation, Normalizing Flows can learn highly expressive models of user or item embedding distributions. They are particularly promising for few-shot or cold-start sequential recommendation tasks, where modeling the uncertainty in a user’s evolving taste is critical.

When to Consider: Normalizing Flows are an advanced generative modeling technique. Consider them for research purposes or in applications where precise density estimation of user preferences is critical. They are generally more complex to implement and train than other generative models.

- Seminal Papers:

- Foundational: Rezende, D. J., & Mohamed, S. (2015). Variational Inference with Normalizing Flows. https://arxiv.org/abs/1505.05770.

- IDNP: Du, W., Wang, H., Xu, C., & Zhang, Y. (2023). Interest Dynamics Modeling with Neural Processes for Sequential Recommendation. https://arxiv.org/abs/2209.15236.

Python Frameworks

- IRGAN: https://github.com/geek-ai/irgan The original implementation is at geek-ai/irgan on GitHub. Implementations are typically done from scratch in core deep learning libraries.

- DiffRec: https://github.com/YiyanXu/DiffRec Research implementations from the seminal papers are available on GitHub at YiyanXu/DiffRec and WHUIR/DiffuRec.

- GFN4Rec: https://github.com/CharlieMat/GFN4Rec The model whose implementations is primarily found in the authors’ research repositories on GitHub.

Production-ready?

- All Models in this Section: Research Interest. This entire category represents the frontier of recommendation research.

- GANs (IRGAN): While conceptually powerful, they are notoriously difficult to train and stabilize, which has prevented widespread production adoption.

- Diffusion (DiffRec): This area is generating significant excitement and strong benchmark results. However, the models are computationally intensive, especially the iterative sampling process at inference time, making low-latency production deployment a major challenge.

- GFlowNets & Normalizing Flows: These are highly promising but complex paradigms that are still in the early stages of exploration for recommendation tasks.

Section 2: Text-Driven Recommendation Algorithms

This section shifts focus to algorithms that explicitly leverage unstructured text, primarily user reviews and item descriptions. The advent of powerful NLP models, especially Large Language Models, has dramatically expanded the capabilities in this domain.

2.1 Review-Based Models

These models mine user-generated reviews to extract rich, nuanced information about user preferences and item attributes. This helps to alleviate the data sparsity and cold-start problems inherent in interaction-only models. The use of text provides a powerful bridge, improving performance and offering a natural pathway to explainability.

Why read the reviews?

A 5-star rating tells you what a user liked, but the review tells you why. One user might give a phone 5 stars for its “amazing camera,” while another gives the same rating for its “incredible battery life.” Review-based models “read” this text to understand these nuances, allowing them to differentiate between users with the same ratings but different preferences, leading to far more personalized recommendations.

2.1.1 DeepCoNN (Deep Cooperative Neural Networks)

Key concept: DeepCoNN uses a dual deep learning architecture. One Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) processes the concatenation of all reviews written by a target user to learn a latent user representation. In parallel, a second CNN processes all reviews written for a target item to learn a latent item representation. These two vectors are then combined to predict the final rating.

Key differentiator: It was a foundational model demonstrating that user and item profiles could be learned end-to-end directly from raw text. Instead of manual feature engineering, it lets the neural networks discover what aspects of language are important for representing users and items.

Use cases: Rating prediction in review-rich environments like Amazon, Yelp, and other e-commerce or content platforms. It is particularly effective at alleviating the cold-start problem, as it can generate meaningful representations from text even when rating data is sparse.

When to Consider: Consider DeepCoNN when you need to leverage review text to improve rating prediction, especially for users or items with few ratings. It is a foundational model that serves as a strong baseline for more advanced text-based models.

- Seminal Paper:

- Zheng, L., Noroozi, V., & Yu, P. (2017). Joint Deep Modeling of Users and Items Using Reviews for Recommendation. https://arxiv.org/abs/1701.04783.

2.1.2 NARRE (Neural Attentional Rating Regression with Review-level Explanations)

Key concept: NARRE enhances the idea of DeepCoNN by incorporating a dual attention mechanism. It learns to identify and assign higher weights to the most useful and informative reviews when constructing the user and item representations, effectively filtering out noisy or irrelevant content.

Key differentiator: The attention mechanism is the key innovation. It not only improves prediction accuracy by focusing on what’s important but also provides a natural path to explainability. The model can highlight the specific reviews that were most influential in making a recommendation, which can significantly increase user trust.

Use cases: NARRE is designed for rating prediction in systems where user reviews are abundant (e-g., e-commerce, service platforms). Its ability to provide explanations makes it valuable for applications where user trust and transparency are important.

When to Consider: Use NARRE when you have a rich dataset of user reviews and want to improve rating prediction accuracy while also generating explanations. It is a powerful tool for building more transparent and trustworthy recommender systems.

- Seminal Paper:

- Chen, C., Zhang, M., Liu, Y., & Ma, S. (2018). Neural Attentional Rating Regression with Review-level Explanations. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3178876.3186070.

2.2 Large Language Model (LLM)-Based Paradigms

The emergence of Large Language Models (LLMs) has created a paradigm shift, reformulating recommendation as a language understanding and generation problem. LLMs can be applied in various ways, from acting as powerful feature extractors to serving as the core recommendation engine itself.

The Paradigm Shift: From Pattern Matching to Language Understanding

Traditional recommenders are expert pattern matchers, finding correlations in a huge matrix of clicks and purchases. LLM-based recommenders aim to be comprehension engines. They can understand the semantic meaning of an item description, infer intent from a user’s natural language query, and leverage vast world knowledge (e.g., knowing that “cyberpunk” is a theme connecting Blade Runner and Ghost in the Shell) to make recommendations based on a deeper level of understanding.

2.2.1 Retrieval-based: Dense Retrieval & Cross-Encoders

Key concept: This paradigm adopts the two-stage “retrieve-then-rank” architecture common in modern information retrieval.

- Dense Retrieval (Bi-Encoder): A fast “retrieval” stage that uses one model to independently encode the user’s query/profile into a vector and another to encode all items in the catalog. It then uses efficient Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) search to find the top-K most similar items from a massive catalog (millions or billions).

- Cross-Encoder: A slower but more accurate “ranking” stage. It takes the user query and each of the top-K retrieved items together as a single input to a more powerful model (like BERT) to produce a highly precise relevance score for re-ranking.

Key differentiator: The separation of concerns between a scalable-but-less-precise retriever and a precise-but-less-scalable re-ranker. This hybrid approach allows systems to search over enormous item catalogs with very low latency while ensuring the final results shown to the user are highly accurate.

Use cases: This architecture is the standard for large-scale recommendation and search systems (e.g., Google Search, YouTube recommendations). It is used to retrieve relevant items from massive catalogs in real-time.

When to Consider: This is the go-to architecture for building scalable and high-performance recommender systems. When you need to serve recommendations from a large item corpus with low latency, a bi-encoder for initial retrieval followed by a cross-encoder for re-ranking is a state-of-the-art approach.

- Seminal Papers:

- Dense Retrieval (Foundational): Karpukhin, V., Oguz, B., Min, S., et al. (2020). Dense Passage Retrieval for Open-Domain Question Answering. https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.04906.

- Cross-Encoders (Foundational): Nogueira, R., & Cho, K. (2019). Passage Re-ranking with BERT. https://arxiv.org/abs/1901.04085.

2.2.2 Generative / Instruction-Tuned

Key concept: This approach reframes recommendation as a text generation problem. An instruction-tuned LLM is given a prompt containing the user’s history, profile, and a specific task (e.g., “Given this user’s past movie ratings, recommend 5 new sci-fi movies and explain why they would like each one.”). The LLM then generates the recommendations and explanations as a coherent, natural language response.

Key differentiator: Its flexibility and zero-shot reasoning ability. The LLM can leverage its vast pre-trained world knowledge to make novel connections and provide recommendations for queries or user types it has never seen before, complete with human-like justifications.

Use cases: Instruction-tuned LLMs are used for a wide range of tasks, including direct item recommendation, generating explanations, and user profiling. Their flexibility makes them suitable for creating more conversational and multi-task recommendation systems.

When to Consider: Consider this approach when you want to leverage the generative and reasoning power of LLMs. It is particularly promising for cold-start problems and for building systems that can perform multiple recommendation-related tasks within a unified framework.

- Seminal Paper:

- Geng, S., Liu, J.,, et al. (2022). Recommendation as Language Processing (RLP): A Unified Pretrain, Tine-tune, and Prompt Paradigm. https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.13366.

2.2.3 RAG & Feature Extraction

Key concept: This paradigm uses LLMs as a powerful component to enhance other recommender systems in two primary ways:

- LLM as a Feature Enhancer: Using an LLM as a sophisticated tool to process unstructured text (reviews, item descriptions) and extract high-quality semantic embeddings or structured features (e.g., “user cares about battery life”) to feed into any downstream recommendation model.

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): Grounding a generative LLM with real-time, factual information. Before generating a recommendation, the system retrieves relevant documents (e.g., up-to-date product specs, user’s recent reviews) and adds them to the LLM’s prompt as context.

Key differentiator: RAG’s key function is to mitigate hallucinations and ensure the LLM’s recommendations are factually accurate and based on current information from a trusted knowledge source. Using an LLM for feature extraction is a highly pragmatic way to inject powerful semantic understanding into any existing recommender pipeline.

Use cases: Use RAG for building reliable generative recommender systems where factual accuracy is critical (e.g., recommending technical products, academic papers). Use an LLM as a feature enhancer to boost the performance of an existing recommendation model by improving its input features.

When to Consider: Use RAG when building a generative recommender to mitigate the risk of the model making things up. Use an LLM as a feature extractor when you have rich textual data and want to create powerful semantic features to boost the performance of an existing model.

- Seminal Paper (Foundational RAG): Lewis, P., Perez, E., Piktus, A., et al. (2020). Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.11401.

2.2.4 LLM Agents & Tool Use

Key concept: This advanced paradigm treats the LLM as a “reasoning engine” or orchestrator that can use external tools. The LLM is given access to a set of functions or APIs (e.g., a search API, a database query, a traditional recommender model). For a complex user request, the LLM devises a multi-step plan and decides which tools to call, in what order, to fulfill the request.

Key differentiator: The ability to autonomously plan, reason, and act. Unlike other paradigms that perform a single, well-defined task, an LLM agent can decompose a complex goal (e.g., “Find me a camera with the image quality of a DSLR but lighter than 500g”) into a sequence of sub-tasks and tool calls.

Use cases: Building next-generation interactive assistants that can handle complex, multi-step goals, where recommendation is just one part of a larger, problem-solving process. The RecMind framework is a concrete example.

When to Consider: This is a frontier area of research and development. Consider building an LLM agent-based system when the user’s needs are complex and cannot be met by a single retrieval or ranking call. This is for building sophisticated assistants that help users accomplish complex goals.

- Seminal Paper (Example Framework):

- Wang, W., et al. (2024). RecMind: Large Language Model Powered Agent For Recommendation. https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.00366.

2.3 Conversational Recommender Systems

This area focuses on creating interactive, multi-turn recommendation experiences, moving beyond the static “recommend and consume” loop.

From Monologue to Dialogue

Traditional recommendation is a monologue: the system presents a list, and the user takes it or leaves it. A conversational recommender turns this into a dialogue. It’s an interactive back-and-forth where the system can ask clarifying questions and the user can provide nuanced feedback, creating a collaborative process that feels more like talking to a human expert. 💬

2.3.1 Dialogue-based Preference Elicitation

Key concept: This is the process of actively asking a user questions in a multi-turn conversation to learn (“elicit”) their needs and preferences, especially when those preferences are unknown (cold-start) or ambiguous. The system maintains an evolving model of the user’s preferences that it updates with each turn of the dialogue.

Key differentiator: It is an interactive and guided discovery process. Instead of expecting the user to know exactly what they want, the system acts like a helpful sales assistant or concierge, asking clarifying questions to progressively narrow down the options and pinpoint the user’s true intent.

Use cases: Conversational recommenders are used in chatbots, voice assistants, and interactive e-commerce platforms where a guided discovery process is beneficial. They are ideal for complex domains with many attributes, like electronics, travel, or real estate.

When to Consider: Implement a dialogue-based system when you need to serve users with no prior history (cold-start) or when the user’s intent is ambiguous and requires clarification. It is highly valuable in domains where users may not know exactly what they are looking for.

- Key Survey Paper:

- Gao, C., Li, Y., et al. (2021). A Survey on Conversational Recommender Systems. https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.06462.

2.3.2 Natural Language Explanation & Critique

Key concept: This focuses on two-way communication about the recommendations themselves.

- Explanation: The system explains why an item was recommended in natural language (e.g., “I’m suggesting this camera because you said you value long battery life.”).

- Critique: The user can provide feedback on a recommendation in natural language (e.g., “That’s a good start, but can you find something a bit lighter?”), and the system uses this critique to refine its next suggestion.

Key differentiator: It creates a collaborative feedback loop. This empowers the user to iteratively steer the recommendation process, which builds trust and leads to a more satisfying outcome than a static, one-shot recommendation. It transforms the interaction from a simple transaction to a partnership.

Use cases: This is a key feature for advanced conversational agents and recommender systems aiming for a high-quality user experience where building user trust and providing a highly interactive, refined search process is important.

When to Consider: Implement natural language explanation and critique capabilities when the goal is to create a truly interactive and user-centric recommendation experience. If user trust is a key concern, these features are essential.

- Key Survey Paper:

- Jannach, D., & Jugovac, M. (2019). Explainable and Conversational Recommender Systems. https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.01735.

Python Frameworks

- Review-Based: These models are typically implemented from scratch or using standard deep learning libraries. The Microsoft Recommenders repo (https://github.com/recommenders-team/recommenders) contains conceptually similar text-aware models for news recommendation (e.g., NAML, LSTUR).

- Retrieval-based: