Automatic Facet Discovery in E-Commerce Search

September 6, 2025

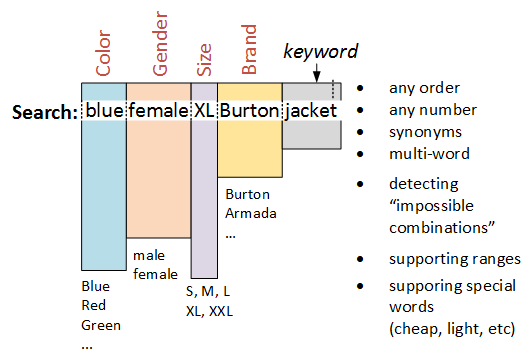

Download PDFThis paper addresses a significant challenge in e-commerce information retrieval: the failure of standard keyword search systems to correctly interpret complex user queries that contain product attributes. Queries such as “blue XL Burton jacket” are often processed as a simple set of keywords, leading to irrelevant results and compelling users to engage in a laborious manual filtering process. We present a proof-of-concept (PoC) for an automatic facet discovery system designed to parse user queries, identify terms corresponding to product facets (e.g., color, brand, size), and apply these filters automatically. This research demonstrates a practical methodology for bridging the semantic gap between unstructured free-text search and structured faceted navigation, thereby enhancing result relevance and improving the overall user experience.

A video demonstration of the system, implemented on the Hybris accelerator platform, is provided below.

1. Introduction

Faceted search is an integral feature of modern e-commerce platforms, fundamentally improving the user’s search and discovery experience. From a user-centric perspective, faceted navigation decomposes search results into multiple, orthogonal categories (facets), each with corresponding value counts. This paradigm enables users to iteratively refine, or “drill down,” into the result set by applying filters in any desired sequence.

The utility of this functionality is particularly evident when interacting with large-scale product catalogs, as it substantially improves product findability, mitigates user frustration, and provides a structured navigational framework. Furthermore, faceted search architectures programmatically generate relevant landing pages for long-tail keyword queries, a long-standing strategy in search engine optimization that was traditionally accomplished through static category pages.

2. A Taxonomy of User Search Queries

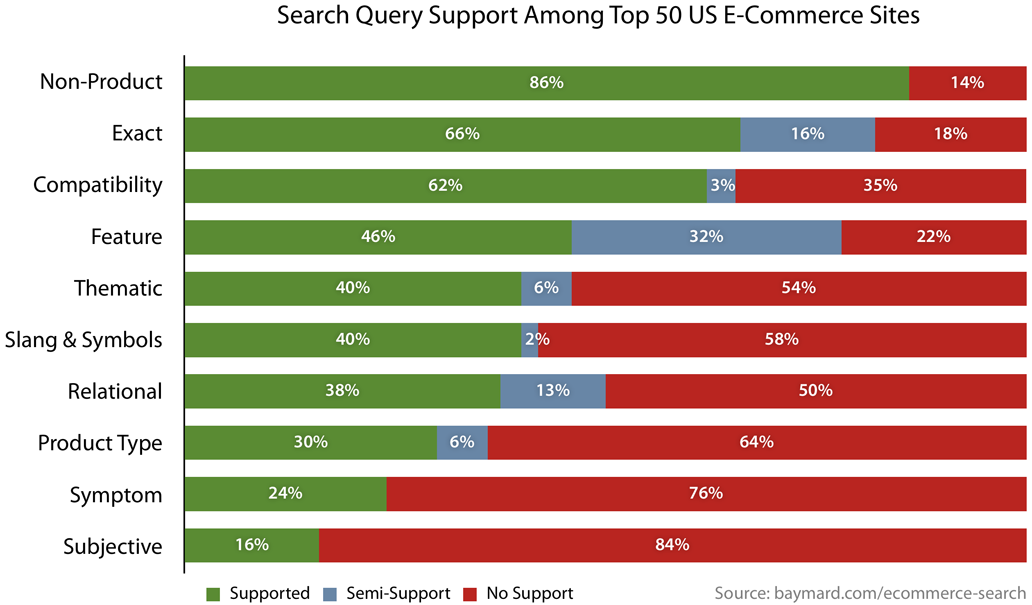

Empirical research from the Baymard Institute classifies user search behavior into 12 distinct query types, the majority of which are inadequately supported by out-of-the-box e-commerce search engines.

- Exact Searches: Queries for specific products via title or model number (e.g., Keurig K45).

- Product Type Searches: Broad queries for product categories (e.g., Sandals).

- Symptom Searches: Problem-based queries where the user seeks a product as a solution (e.g., “stained rug”).

- Non-Product Searches: Informational queries regarding policies, company details, or help documentation.

- Feature Searches: Queries specifying particular product attributes (e.g., Waterproof cameras).

- Thematic Searches: Queries for abstract or conceptual categories with ill-defined boundaries (e.g., “Living room rug”).

- Relational Searches: Queries based on a product’s association with another entity (e.g., Movies starring Tom Hanks).

- Compatibility Searches: Queries for products compatible with another item (e.g., Lenses for Nikon D7000).

- Subjective Searches: Queries using non-objective, qualitative terms (e.g., “High-quality kettles”).

- Slang, Abbreviation, and Symbol Searches: Queries employing linguistic shortcuts (e.g., Sleeping bag -10 deg).

- Implicit Searches: Queries that omit context-dependent qualifiers (e.g., searching Pants when intending Women’s Pants).

- Natural Language Searches: Queries formulated in complete sentences rather than keyword sets (e.g., Women’s shoes that are red and available in size 7.5).

While platforms such as Hybris provide foundational support for some of these query types, the implementation often lacks the necessary sophistication for accurate intent interpretation. Neither Hybris nor its underlying SOLR search engine can natively associate query terms with semantic concepts like product features or categories. By default, all input is treated as a simple keyword query. The proposed PoC serves as a semantic bridge between these free-text queries and the platform’s powerful faceted search capabilities, thereby addressing many of the aforementioned query types more effectively.

3. The Challenge with Conventional Faceted Search

Conventional faceted search implementations present known usability challenges. Although platforms like Hybris display facets relevant to an initial query, the presence of attribute-related terms within the query itself can paradoxically cause those same facets to be excluded from the results.

For instance, in the query “blue armada jacket XXL,” a standard search engine processes all four terms as a free-text request, returning only documents containing all four keywords. This approach is fundamentally flawed, as product attributes are often stored internally in structured formats or with distinct internal codes, necessitating duplicate index fields for their textual representations.

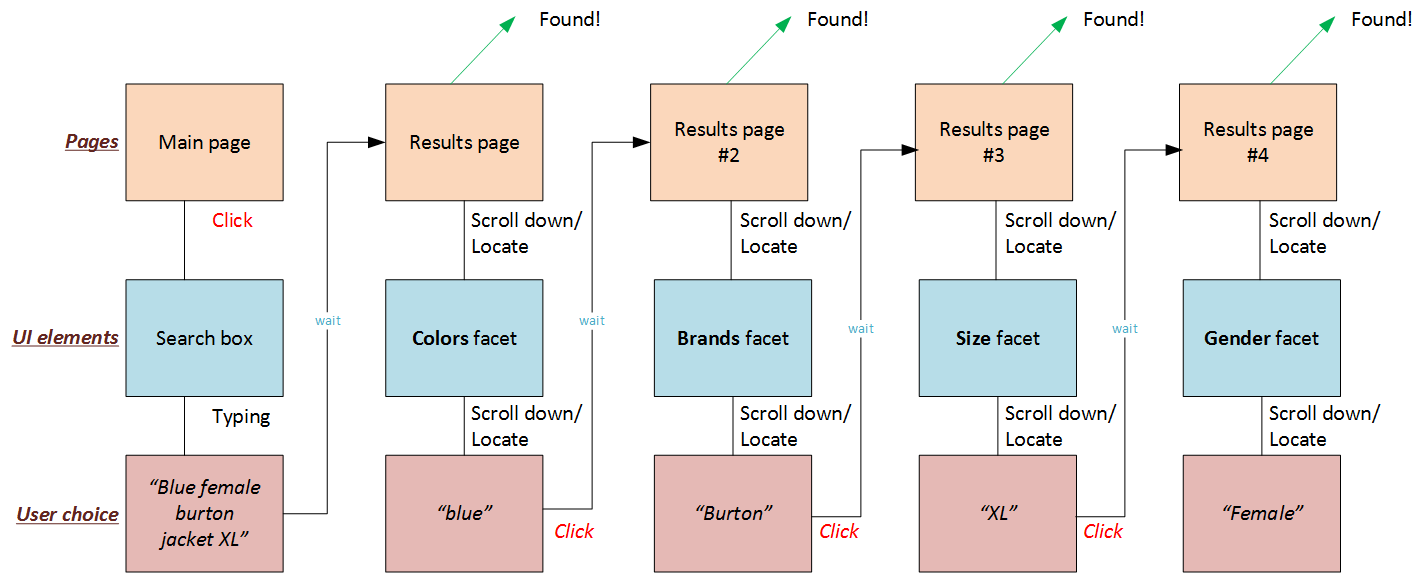

The primary issue is the significant divergence between search results and user expectations. A query for “blue armada jacket XXL” will retrieve products that simply contain these keywords in their title or description, a limitation that encourages merchants to engage in keyword stuffing to improve findability. This leads to a cumbersome, multi-step user journey to locate a specific product:

- Execute initial search: User enters the query “blue female XL Burton jacket.”

- Apply Color facet: User locates and selects “blue” from the color facet list.

- Apply Brand facet: User locates and selects “Burton” from the brand facet list.

- Apply Size facet: User locates and selects “XL” from the size facet list.

- Apply Gender facet: User locates and selects “Female” from the gender facet list.

This iterative process requires multiple user interactions and page reloads. While some platforms like Google Shopping have implemented automatic facet application, this functionality is not standard in most e-commerce solutions.

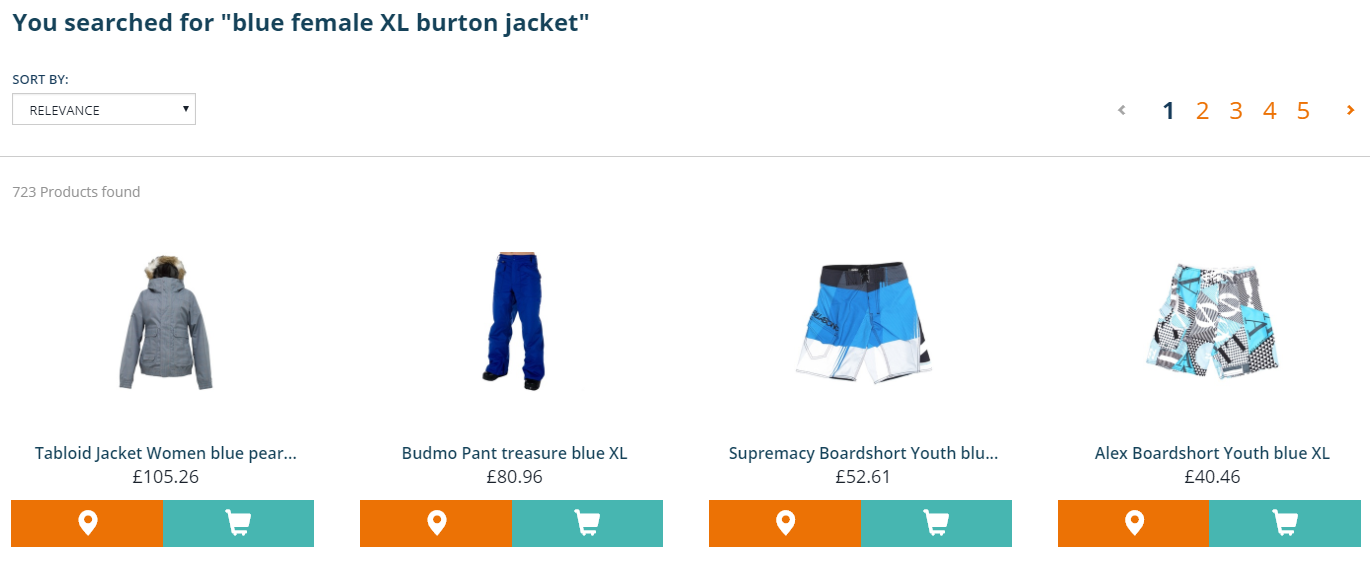

A default SAP Commerce implementation, for example, yields highly irrelevant results for the query “blue female XL Burton jacket”:

How SAP Commerce Cloud works out-of-the-box (the default configuration).

How SAP Commerce Cloud works out-of-the-box (the default configuration).

- Observation: The results include items that are not jackets, not blue, not for women, and mostly not from the specified brand.

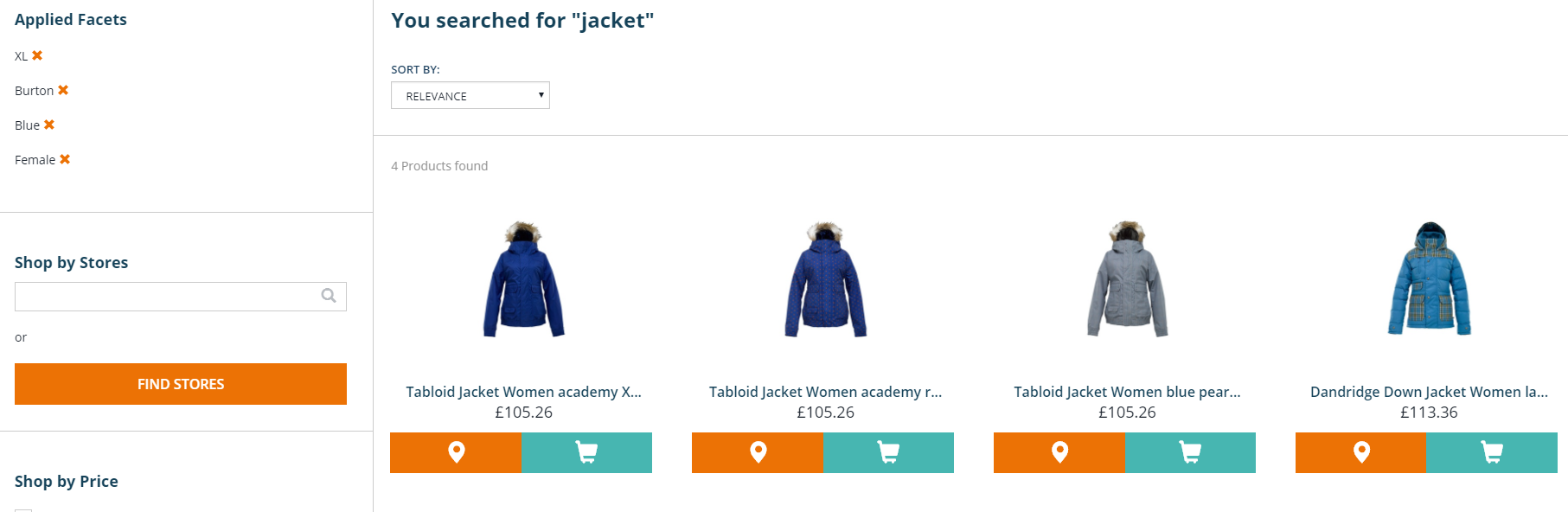

In contrast, the proposed PoC delivers highly relevant results for the identical query:

Performance of the proposed PoC for the query “Blue burton female XL jacket”.

Performance of the proposed PoC for the query “Blue burton female XL jacket”.

- Observation: All resulting products are blue, female jackets from the Burton brand.

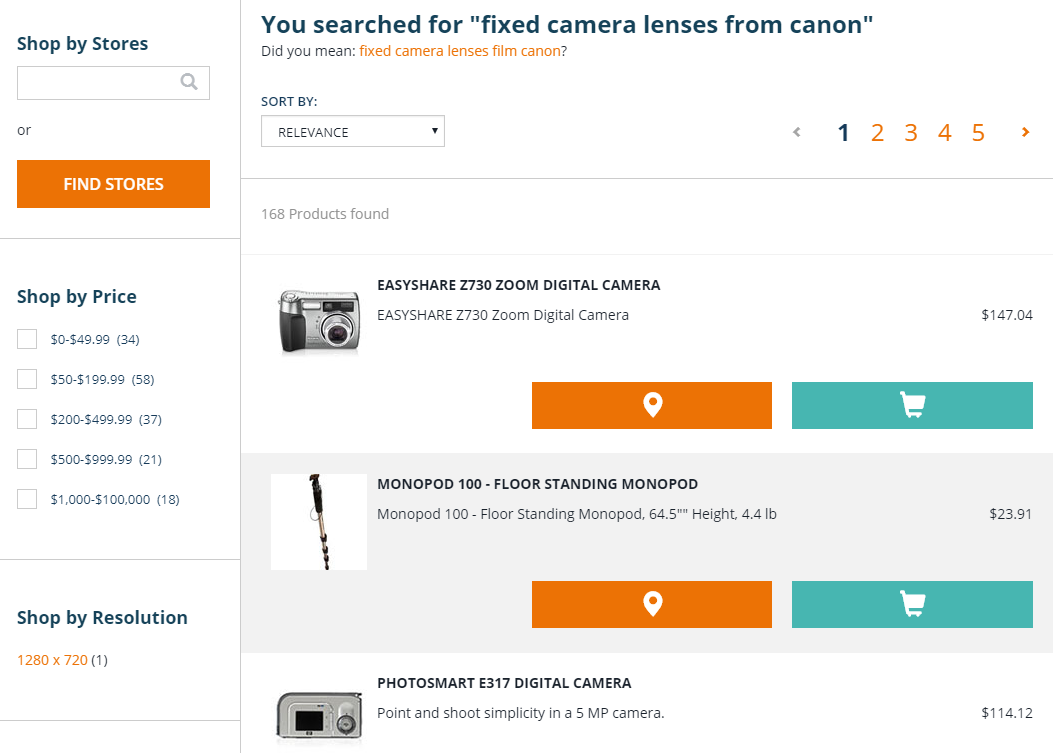

This performance improvement is consistent across different product domains. For an electronics catalog, the query “fixed camera lenses from canon” on a standard system yields irrelevant products:

Standard SAP Commerce search performance for the query “Fixed camera lens from Canon”.

Standard SAP Commerce search performance for the query “Fixed camera lens from Canon”.

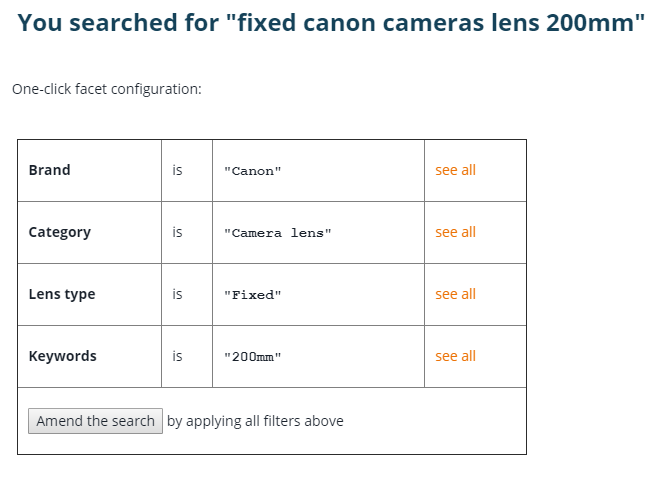

The proposed system, however, correctly identifies and filters for the requested products:

Performance of the proposed PoC for the query “Fixed camera lens from Canon”.

Performance of the proposed PoC for the query “Fixed camera lens from Canon”.

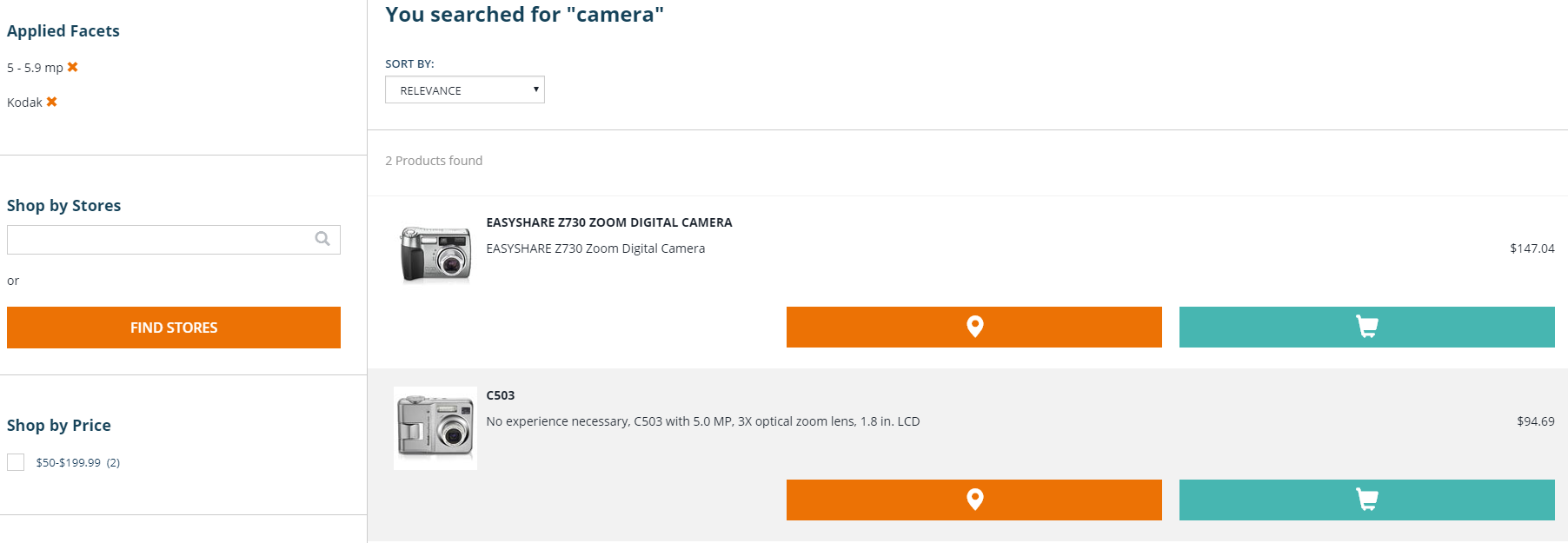

The system can also interpret numerical ranges. A query for “5 mp kodak camera” correctly applies a filter for the “5-5.9 Mp” facet range.

The PoC applying a facet range for the query “5 Mp Kodak camera”.

The PoC applying a facet range for the query “5 Mp Kodak camera”.

4. Implementation Strategy: Automatic vs. Suggested Queries

While the PoC implements fully automatic query interpretation, a production deployment would benefit from A/B testing to determine the optimal strategy for a specific business context. Factors such as catalog structure, product diversity, and user profiles should inform this decision.

An alternative, non-automatic approach involves presenting the interpreted query as a one-click suggestion alongside the standard keyword search results.

This method provides user control while still leveraging the benefits of query interpretation. If implemented, the suggestion interface should be designed to be both compact and informative.

5. Technical Architecture and Implementation Details

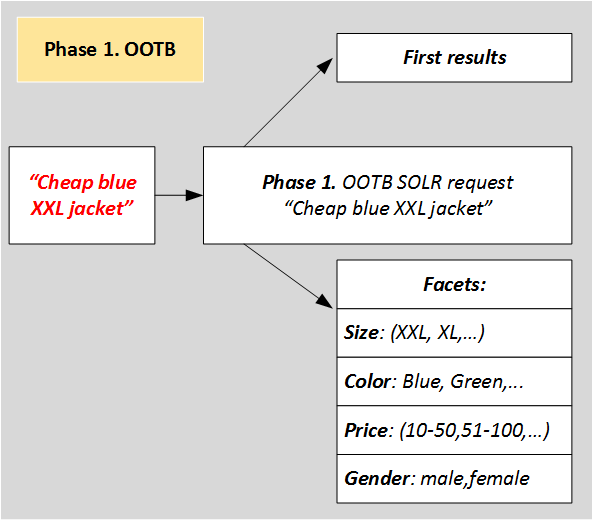

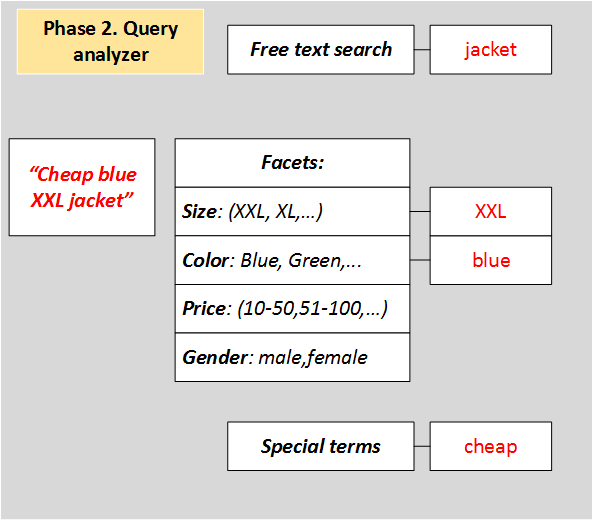

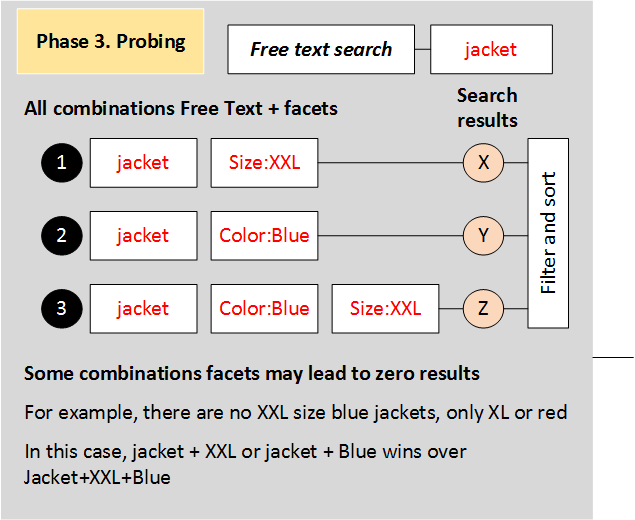

The system operates by analyzing the input query to extract terms that correspond to known facet values. A primary technical challenge is resolving ambiguity when a query contains conflicting or mutually exclusive facet terms. For example, the query “Canon flash memory” is ambiguous if the product catalog contains no flash memory manufactured by Canon. The system must then infer user intent: is the brand “Canon” or the category “Flash memory” the primary constraint?

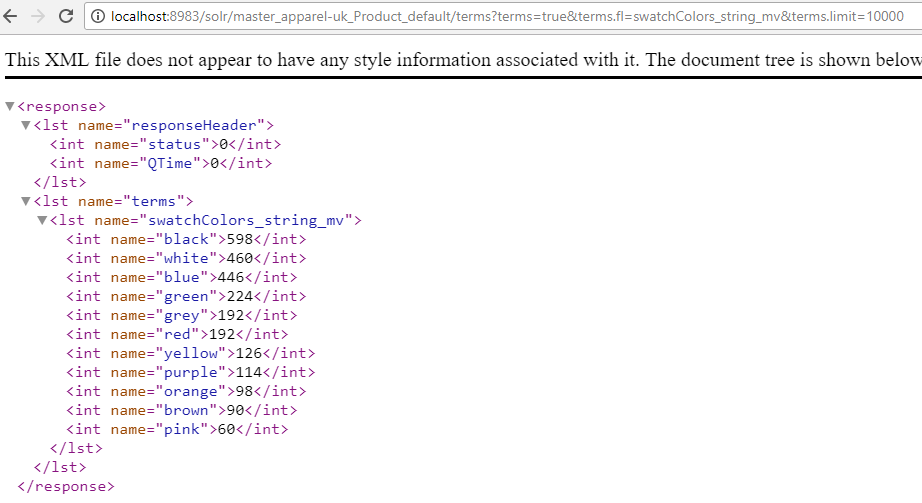

This ambiguity is resolved when the catalog contains products that satisfy all specified attributes. For instance, if the catalog contains Sony-branded flash memory, the query “Sony Flash Memory 32Gb” is unambiguous, allowing the system to confidently apply facets for brand, category, and storage capacity.

To facilitate this mapping, the system maintains an in-memory representation of all available facet values. These values are retrieved directly from the SOLR index using its built-in “terms” request handler, which provides an efficient method for obtaining a complete and uniform list of facet terms.

For optimal performance, this technique requires SOLR fields configured with a KeywordTokenizer (to preserve multi-word facet values) and without stemming filters (to ensure exact matching). This can be achieved by creating dedicated, non-stemmed copy fields or by changing the field type to string, though the latter may have minor implications for full-text search relevance.

The PoC employs an efficient strategy by only processing facets that are returned by an initial standard keyword search, rather than analyzing all possible facets in the entire catalog.

Once terms are mapped to facets, the remaining query words are categorized as stopwords, special commands (e.g., “cheap”), or residual keywords for the free-text search component.

The system then constructs a new, hybrid query combining the discovered facet filters with the remaining keywords.

To handle conflicts where a term matches multiple facets (e.g., “red” as a color vs. part of the brand “Red Hat”), the PoC implements a simple disambiguation logic: it executes a count for each interpretation and proceeds with the option that yields a non-zero result set. If both interpretations are valid, or if both yield zero results, the system defaults to a standard keyword search. More advanced implementations could prompt the user for clarification.

The system is designed to support dynamic facet configurations in SAP Commerce without requiring manual reconfiguration. However, it does not yet handle complex natural language constructs (e.g., “with,” “or,” “without”), which would require more advanced natural language processing techniques.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

This paper has presented a proof-of-concept for an automatic facet discovery system designed to address a prevalent limitation in e-commerce search engines. By programmatically parsing unstructured user queries to identify and apply corresponding structured facet filters, the proposed system effectively bridges the semantic gap between keyword-based retrieval and faceted navigation. The experimental results demonstrate a significant improvement in result relevance and a more streamlined user experience compared to standard search implementations.

The current implementation, while promising, has several recognized limitations that provide clear directions for future research. The system’s reliance on exact-match string comparisons for facet mapping is inherently brittle and does not account for synonyms, morphological variations, or misspellings. Furthermore, the conflict resolution logic for ambiguous terms is heuristic-based and could be substantially improved. The PoC does not yet support complex linguistic constructs (e.g., conjunctions, prepositions) or handle redundant terminology within queries.

Future work will focus on integrating more sophisticated Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques to overcome these challenges. The exploration of libraries such as OpenNLP is underway to incorporate capabilities like stemming, synonym expansion, and dependency parsing for a deeper understanding of query syntax and semantics. Further research will also involve developing a more robust disambiguation model, potentially leveraging machine learning trained on historical search logs to predict user intent more accurately. Finally, a quantitative evaluation through rigorous A/B testing and formal user studies is required to measure the system’s impact on key performance indicators, such as search success rate, session duration, and conversion.

Ultimately, the continued development of such intelligent query interpretation systems is a critical step toward creating more intuitive, efficient, and user-centric information retrieval experiences within the e-commerce domain.